Tribal first responders and mental well-being: An invisible minority

October 19, 2021

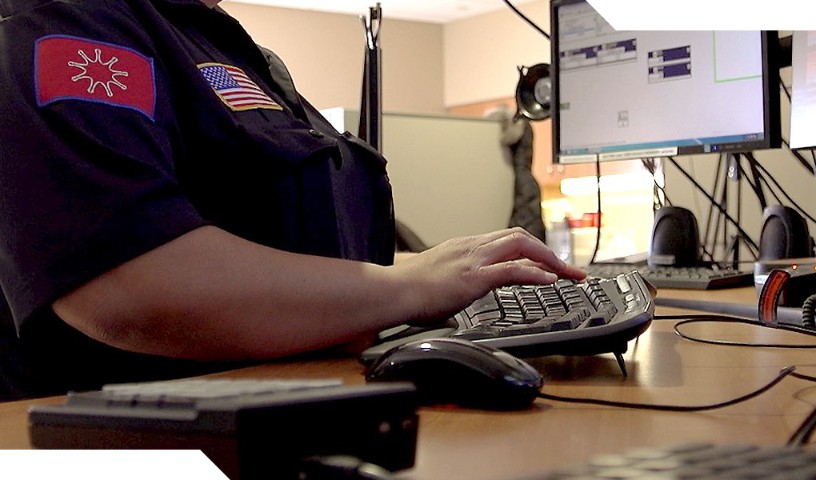

First responders are critical for the well-being of those in their community. But too often, their mental health needs go unattended. This is especially true within the Native American community. Tribal first responders don’t often get to take part in the conversation when it comes to mental health resources. This includes counseling, crisis intervention, and hotlines.

More than 200 police departments operate in “Indian Country” – a term used to encompass all federally recognized tribes in the United States[i]. These departments range in size from 2-3 officers to more than 200 officers[ii]. Differences in tribal territory and population size account for this range. For example, the Havasupai Tribe near the Grand Canyon in Arizona has a population of about 600 tribal members. The Navajo Nation, which spans across Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah, has a population of about 173,000 tribal members.

The large differences in population also play a role in staffing. This can create immense stress for police officers who have a heavy workload compared with tribes with a smaller land boundary. However, even if a tribe has a smaller population, it does not guarantee police officers won’t have their hands full.

Violent crime rates

Native Americans – and Native women in particular – face the highest violent crime rates out of any other ethnicity in America[i]. On average, police officers witness 188 critical incidents during their careers. And this exposure can lead to Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and depression, which officers are five times more likely to have[ii].

So, what does this mean for tribal officers? The chance of mental illness among Tribal first responders is higher than non-tribal officers.

Many of the tribal officers are Native members of the communities they serve. They respond to calls with people they may have close ties with, which can cause unique mental stressors. Joel Zuniga, Tribal Police Sergeant for the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony, has first-hand experience.

Responding to family

Sergeant Zuniga has been a police officer for 17 years, all of them spent with his own tribe. He was born and raised on the reservation. There is hardly a call he responds to that does not involve someone he knows. The most trying of these calls, are the ones that involve his own relatives.

“One of the hardest calls I’ve had to respond to, was one that involved a family member,” said Sergeant Zuniga. “As I approached the street where the caller had seen an inebriated male, I found my father. Immediately I radioed in to alert my supervisor of the situation who told me to head back to the department once another officer could take the scene over. The shame and embarrassment I felt definitely took a toll on my mental well-being. And even today I am stricken with bouts of fear that my next shift might be the one where I respond to a shooting or stabbing, and the victim, or perpetrator, is a loved one.”

Sergeant Zuniga’s experience is indicative of the unique nature of policing in Indian Country, and it is a harrowing example of the mental health toll tribal officers experience.

The need for mental health resources

These personal accounts demonstrate the need for mental health resources tailored to tribal first responders. Leadership and personnel need to come together to set up a work environment that provides training to help improve the mental health, resiliency and wellbeing of Tribal first responders.

This solution seems straightforward. But there is a culture of ‘stoicism’ when first responders witness a traumatic event. One way to combat this culture is to have clear written protocols and strategic plans that allow first responders to feel more in control of their environment. This could include debrief sessions with team members and superiors, peer to peer support, and integrating Native American traditions into the way officers deal with traumatic events.

Teamwork and a sense of community serve as a protective factor for first responders[i]. A high sense of team accomplishment and assurance of personal and team capabilities were associated with lower stress levels[ii]. The Native American sense of community and tradition provide protective factors for public safety officers. They also provide an excellent vehicle for addressing mental health risk factors.

Using traditional healing

The National Institutes of Health/National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine identifies Native American traditional healing as a medical system that uses a range of holistic treatments by indigenous healers for a variety of acute and chronic conditions, and to promote health and wellbeing[i].

Native American healers add a cultural perspective to aid the Tribal first responders’ mental wellbeing. While there are individual tribal differences, there are also shared health beliefs and interventional strategies – including a health promotion foundation that embraces bio-psycho-socio-spiritual approaches and traditions[ii].

Bio-psycho-socio-spiritual approaches include stories and legends. These help teach positive behaviors and the consequences of failing to observe the laws of nature. Many indigenous healers use oral traditions to discuss difficult topics. The use of stories and legends provide the recipient with ways to cope and help provide a renewed sense of self. It is well documented that storytelling is an effective means for coping with traumatic events and provides an opportunity of relationship building and community building for the tribe as a whole.

Bio-psycho-socio-spiritual approaches also include herbs, manipulative therapies, ceremonies, and prayer. These are used in various combinations to prevent and treat illness, both physical and mental[iii]. These practices follow a synergetic approach that Native American cultures appreciate.

First responders everywhere sacrifice their mental well-being to ensure the safety of their communities. But tribal public safety see unique challenges.

Tribal public safety can help close the gap in addressing mental health among tribal first responders by integrating traditional Native American strategies for coping, establishing departmental plans and policies, and identifying resources tailored for tribal populations.

Makai Zuniga, a tribal member of the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony, recently graduated from the University of Nevada, Reno with his B.A. in Political Science. He spent the summer of 2021 interning with FirstNet Program at AT&T, with a focus on tribal affairs.

1 Federal Bureau of Investigation. (n.d.). Tribal Law Enforcement. Tribal Law Enforcement Resources.

2 Federal Bureau of Investigation. (n.d.). Tribal Law Enforcement. Tribal Law Enforcement Resources. Federal Bureau of Investigation. (n.d.). Tribal Law Enforcement. Tribal Law Enforcement Resources. https://www.tribal-institute.org

3 Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2016, June 23). Overview of Tribal Crime and Justice. National Institute of Justice. https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/overview-tribal-crime-and-justice#note2

4 Hilliard, J. (2020, November 20). New Study Shows Police at Highest Risk for Suicide Than Any Profession. Addiction Center. https://www.addictioncenter.com/news/2019/09/police-at-highest-risk-for-suicide

5 Quevillon, R. P., Gray, B. L., Erickson, S. E., Gonzalez, E. D., & Jacobs, G. A. (2016). Helping the helpers: Assisting staff and volunteer workers before, during, and after disaster relief operations. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 72(12), 1348–1363. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22336

6 Brooks, S. K., Dunn, R., Amlot, R., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. (2016). Social and occupational factors associated with psychological distress and disorder among disaster responders: A systematic review. BMC Psychology, 4, 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-016-0120-9

7 NIH National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. CAM Basics. Publication 347. [February 27, 2010]. Available at: http://nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam/

8 Koithan, M., & Farrell, C. (2010). Indigenous Native American Healing Traditions. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 6(6), 477–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurpra.2010.03.016

9 Cohen K. Honoring the medicine: An essential guide to Native American healing. New York, NY: Ballantine Books; 2006.